|

I’ve tried to write this article a few times, but each time I stop myself because parts of the discussion feel a bit stupid, but this is a great point to start with, maybe there’s a separate article in it later down the track. For me as a 38 year old, there’s often a tricky hump to get over when discussing games, which is the lack of emotional maturity in video games. This is largely down to games being a young medium as I’ll discuss further on, but in the last 10-15 years we’ve seen the issue is trickier than that, as many people have tried to create more emotionally mature games with varying levels of success. On the whole storytelling has gotten much better, but I believe there’s been some big mis-steps with games like Dear Esther and the like being so revered when they unfortunately do nothing to bridge the divide between storytelling and gameplay (ie their gameplay has nothing to do with their story). The notable exception being the Giant Sparrow games, Unfinished Swan and Edith Finch which are both definitely a step in a better direction, recognising at least in part that gameplay should do the telling.

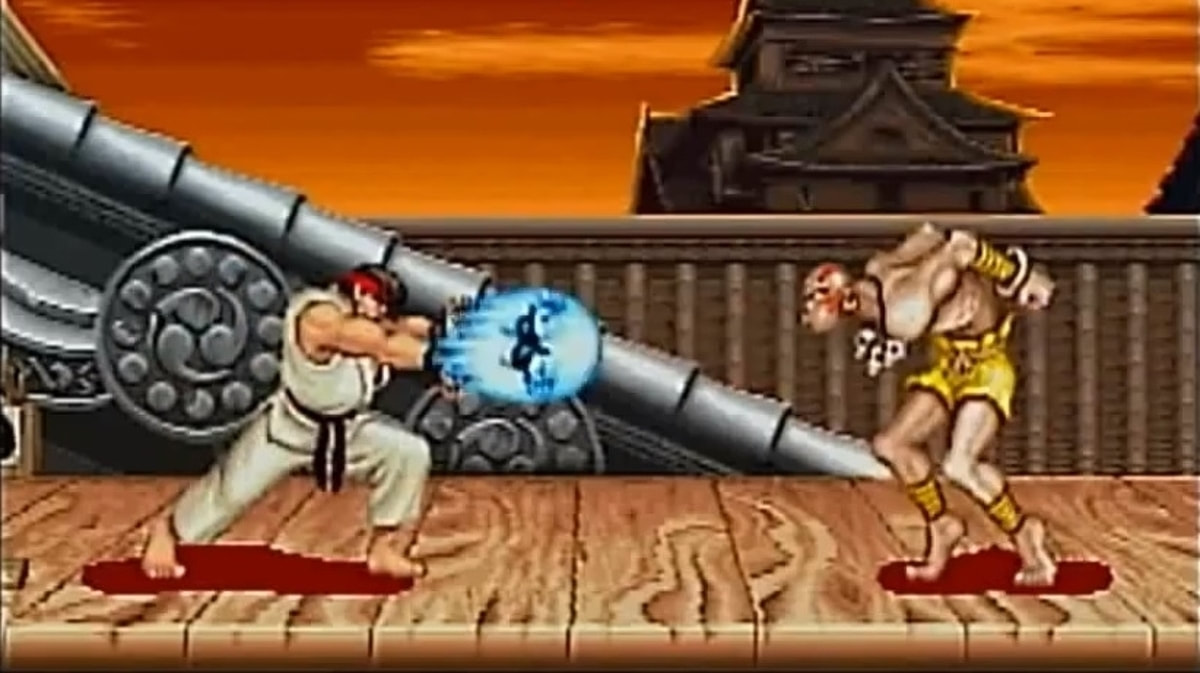

So the flip side that I learned from some of Dear Esther’s ilk is that sometimes the attempt to be emotionally mature can leave a very bad taste, so this has given me a new appreciation for the time and place to be dumb, fun and simple. So I guess that’s a bit of an on-ramp for some of the stuff I don’t feel completely comfortable talking about in-depth, but that’s one of the enduringly strange things about video games is that we constantly end up analysing and referencing things like a plumber and his mushrooms and turtles. In a previous post you mentioned how games are still such a young medium. Let’s explore that Well this depends on the framing so I’ll jump back a bit into my personal history. Although the bulk of my formal education was not in games (my undergrad was in music technology) I was lucky enough to have some experience being immersed in gaming academia during my PhD. One of the key things I learned very quickly was that when games are taught at a university level, they are never just talking about video games, they’re considering the whole human history of games: everything from ancient boardgames to sports to video games. So in that sense games are not a young medium at all, and while video games do represent a huge shift, I’ve found that the more I open my mind to the history of human games and “play”, the less it seems like video games are as much of a great leap forward as they seem. What I mean by that is, as I grow as a game designer and I read insights from other game designers, I find more and more that foundational principles “discovered” by video game designers – eg rules about game balance, scope, constraints, risk versus reward etc – have already long existed in board games and sports. And I say this from my own experience of gradually discovering rules, tools and constraints that work for me, that I could have come to much sooner had I opened my mind to taking inspiration from board games, sports, and “play” in the even broader sense of engaging with any aspect of life in a playful way, rather than taking inspiration only from video games. To give a few examples, the developers of FTL: Faster Than Light had a very strong board game influence, which led to them really crystallising the game down into its simplest components, as they had such a deep appreciation for what could be done with a single static game-board. In a very different way, the game Myst was inspired by DnD, to the extent that they role-play/improvised the game as a DnD scenario, to flesh out the world and identify any potential issues before going into full production. But in both cases non-videogame influences made these games much richer and more focused experiences. When I design games, I’m guilty of leaning too heavily on my knowledge of video game history. This is an easy trap to fall into, because as one becomes more and more of an expert one’s ego loves to revel in its encyclopaedic knowledge. But on a good day I’ll catch myself and do better to get some perspective. I at least have the regular touchstones of chess and Lewis Carroll’s story Through the Looking Glass. While I’m not a chess player at all I have an ingrained feel for the rules and the possibility space, and combined with Through the Looking Glass I like to imagine a story space that can unfold by the intricate interactions of just a few simple rules. And it matters to me because it lasts. Like great music, great games should be able to last hundreds or thousands of years. But will many video games last? I wonder if the more complex a videogame’s ruleset, the less likely it will stand the test of such long periods of time. Just speculation, but it’s easy to imagine say Tetris still being popular hundreds of years from now because of it’s pure and simple ruleset. On the flipside, only a decade or two ago one might have assumed the same for realtime strategy games, but curiously they disappeared, or at least were subsumed by other genres. But it’s hard to imagine many other games that really strike such a resonant chord, especially the majority of contemporary games that are often a complex jumble of many different influences and gameplay styles. Anyway, whether a game can last a thousand years is not as important as what in can contribute in the here and now: if a game only lasts 5 years but it inspires thousands or millions of designers and players and helps evolve the practice, that’s what matters most. So I guess the point here is to continually recognise what the fundamentals are – sometimes appreciating why they last, and sometimes having a feel for why they need to change. So getting back to the title, lets explore what you mean by Quantum Leaps As I mentioned in a previous post, despite games being a young medium there are countless examples of games that represent “quantum leaps” ahead. There are really so many of these now that it depends on your framing as to what constitutes a quantum leap e.g. this could be explored in the realms of the commercial, technical, gameplay dynamics, rulesets, etc I’m not really interested in exploring any one particular avenue but really just exploring a few examples that have succeeded in many of those respects, and I guess a personal reflection of the kind of miraculous sense of how these things came together, that all the disparate ingredients locked into place. Super Mario Bros There’s not much a need to say about this that hasn’t been said a million times before, but really this is the game that set the standard for what a quantum leap ahead looks like. I was born in 1982 and this game came out in 1985, so given the timelines I was more of a Super Mario 3 fan, and always found the original’s controls to be a little too janky. But every now and then when I take a look back at this game, I’m often surprised that things that I thought originated in Mario 3 actually came from the original. To me that’s where its significance matters perhaps most of all, in the fact that it went above and beyond. The foundation of it was already a great game, but they made it incredible by combining imaginative flights of fancy with deeply grounded gameplay legibility, a contrast that has played out through every Mario title since and which arguable is so compelling in itself that the series continues to get away with little-to-no story. Street Fighter II Street Fighter II’s crystallization is, for me, much more dramatic than Mario’s. Maybe platform games were already established in a more primitive sense (eg Donkey Kong) and because there’s a lot you can do with platformers, there’s a lot of ways to approach them and introduce more or less puzzle or arcade elements, etc, etc, but the one-on-one fighting game almost begins and ends with Street Fighter II and very few things in that genre have proved an enduring value add, which is arguably why games in the genre continually rely on huge player rosters and massive (or bizarre) visual spectacle as their site of innovation. So what did Street Fighter II crystallise? First of all getting the scale of characters on-screen. This is a big deal in any genre with a fixed-offset camera, but there seems to be less margin for error in fighting games. It not only helps with the precision of timing your moves, but it also helps to sell the visual identity of each character, and Street Fighter strikes an amazing balance of iconic characters. It would be easy to say any good character designer could come up with 100 diverse new characters like that, but when you look at say Tekken or the King of Fighters series, are those characters really iconic and stand the test of time in the same way? Is each one really dramatically unique? Sure it was a simpler time when Street Fighter II was released and so the 8 playable characters and 4 bosses was enough, which of course it wouldn’t be anywhere near enough now. But easy to see that having such a small cast of characters allowed each to be intimately crafted, and that in more modern games with larger casts, this just gets diluted. Though the cast definitely shows its age in terms of only having one female character. For contrast, look at some of the characters in Street Fighter V like Abigail or Fang, their over the top designs would be more at home in a King of Fighters or even Guilty Gear game. Secondly, gestural controls are a big one. For me as a designer, whenever I think about creating some kind of a gestural input, my first thought is Ryu’s famous ‘hadouken’ gesture (and side note I always loved how perfectly the hadouken “slide down to right” gesture pairs with its animation of drawing in and pushing out the energy-ball). But this is definitely more of an alpha-and-omega* thing in that it seems like such a great idea, and works so well in this game, but if you try and implement it in your own game you quickly discover that the gestures used in Street Fighter II are pretty much the only ones that can work, at least with a traditional joystick or controller. It seems weird, but there’s just about nowhere else to go from there. Beyond that, there’s so much more, the music, the scenery, the UI slow-motion knock-outs, the jump height, play speed, all of which have been refined over the years throughout the genre, but never with significant deviation from the blueprint that was this game. I don’t say all this as a fighting game fan, but as someone who marvels at how powerful and resonant this perfected form can be when discovered (and how the perfected form can continue to be perfected!) Maniac Mansion Ok so commercially it’s not even remotely in the same ballpark as Mario and Street Fighter, and certainly not as beloved as designer Ron Gilbert’s later Monkey Island (arguably the alpha and omega of comedy-adventure games), but a landmark game nonetheless. Maniac Mansion didn’t crystallise things in the same way as Street Fighter II, and I’d happily argue that Monkey Island and others sanded down those rough edges and failed experiments, but some of Maniac Mansion’s failures are what makes it a great counterpoint to this argument. I’m sure most designers could agree on, and I’ve heard Ron Gilbert himself discuss, issues with the design of this game: too many characters to choose from, too many action-command/verbs, too many baffling things that can go wrong (characters can get killed or captured with little warning, items can be used in “wrong” ways, necessitating a restart of the game), all of which were identified and fixed not just by Lucasarts, by in the genre as a whole. But apart from these remaining issues, Maniac Mansion crystallised the point and click adventure interface (it wasn’t the first, but it was the first to do it well), before that, most adventure games still required you to type in what you wanted your character to do. And so much more was packaged into Gilbert’s SCUMM system, the adventure game engine created for Maniac Mansion that became the basis for so many famous adventure games to follow. The history and innovations of SCUMM are well worth delving into if you’re interested in storytelling or adventure systems. So while point and click adventures have, at least commercially, gone extinct, the legacy started by Maniac Mansion has endured and evolved through influential games like Monkey Island, and highly innovative titles like the musical adventure Loom which was a key reference in my own PhD research into musical gameplay. So let’s unpack *Alpha and Omega I’ve already said a lot so I’ll keep this brief. Street Fighter II is the main game that got me thinking about this: genres, ideas or concepts that begin and end with a certain game. As I discussed above, the one on one fighting genre begins and ends with Street Fighter II, ie I would argue there has not been another quantum leap in the genre since that game, there have only been incremental refinements, and some unsuccessful tangents (eg Tobal and Toshinden notably tried to break the fixed-axis gameplay, but in both cases it didn’t stick). To a lesser extent, 2D platformers all live under the shadow of Super Mario, but this genre successfully made the transition to 3D where I would argue that Mario doesn’t reign supreme (after recently replaying Mario 64 I can’t believe it’s still held in such high regard as the controls, especially the camera, are frustrating beyond belief, though I give props to the star-collection system and hub-world of the castle) Maniac Mansion is the exception as the genre still had more latitude to continue to innovate after this, but as I mentioned there’s something definitive about the original Monkey Island, some magical combination of the genuine sense of adventure combined with the humour (some truly timeless comedy moments, like picking up the idol from underwater or the “confetti/wax lips” sequence), fourth wall breaking before it was cool, all mixed with the lo-fi aesthetic of its time. The sequel was great, but its terrible ending almost serves to say that as fun as the ride was, the original really said it all. So alpha and omega matters to me, because it’s important to know when to move on. If something begins and ends with a definitive game, maybe a radical change is needed. Thanks for reading. Feel free to say hi in the comments and sign up to Lamplight Forest for updates on our games

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed